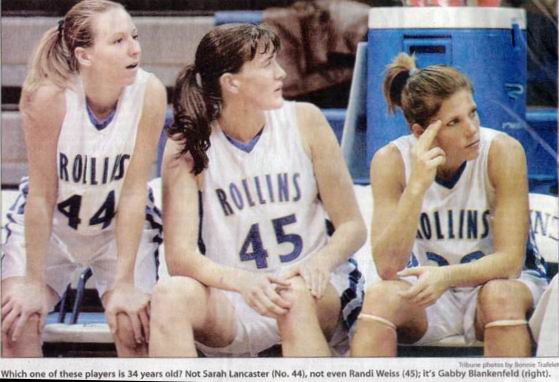

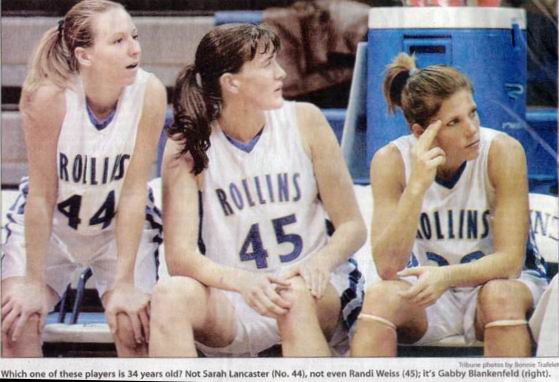

34-year-old college kid lives hoop dream--finallyBy Alan SuttonTribune staff reporter December 12, 2002 WINTER PARK, Fla. -- The name "Gabe Blankenfeld" might ring a bell among followers of the girls sports teams at Naperville Central High School. She was a softball and basketball star for the Redhawks in the mid-1980s, and her name is among those on a plaque in the school trophy case honoring Naperville Central's 1,000-point scorers. Blankenfeld had aspirations of playing in college, but her parents' divorce prompted her to put those plans on hold. Basketball gradually faded from her life as well. It was in February 1986 that Gabe Blankenfeld played her last game for Naperville Central, a two-point loss to Immaculate Heart of Mary in an IHSA sectional final. Nearly 16 years later, 5-foot-9-inch Gabby Blankenfeld is a scholarship player at Rollins College, a Division II powerhouse. Gabe and Gabby are one and the same, and what a long, strange trip it has been from 18 to 34. "This level of play and at her age," Rollins coach Glenn Wilkes Jr. said, shaking his head. "It's astonishing." There have been older college athletes. In last season's NCAA Division II women's golf finals, Judy Street helped Barry University to an eighth-place finish--at 61. Maybe the most prominent "older" college athlete is former Florida State quarterback Chris Weinke, who was 28 when he won the Heisman Trophy in 2000. But few have had a journey like Gabrielle Blankenfeld's. There were scholarship offers from Illinois State to Alaska-Fairbanks after high school, but Blankenfeld's parents had split up before her senior year, drastically altering her future. "What we thought was a pretty together family wasn't," Blankenfeld said quietly. "It was traumatic. My mom had to go back to work and support me, pay the bills. "I would just look into her eyes. I felt bad for her. I couldn't bring myself to leave. I felt like I would be abandoning her." Her mother, Sue Berndtson, who has remarried and still lives in Naperville, remembers it as "a very difficult time." "I always felt that she had to do what was best for her," Berndston said. But college basketball suddenly didn't seem so important to Blankenfeld. "I decided to stay back here, help out," she said. "Everyone was quite surprised. But given the same set of circumstances, I would do it again. I put the basketball down and didn't play again for 10 years." She worked at a small travel agency, then moved to Texas to work for American Express and join her boyfriend. That didn't last. Her sister, Stacey, thought it would be a good idea for the two to spend some time together "before we both got married," so Blankenfeld joined her in Southern California. She played golf and tennis, ran the L.A. Marathon and immersed herself in the martial arts, earning a black belt in karate. Then came the Women's National Basketball Association and open tryouts with the Los Angeles Sparks. Though Blankenfeld hadn't played in years, her sister encouraged her to give it a try. "I went and got a basketball," Blankenfeld said. "Seriously, I didn't have one." She was in for a shock. The players were much bigger and stronger than she remembered. And the WNBA wasn't interested in her. "I wasn't really surprised," she said. "But I was disappointed." Kevin Wilson, a personal trainer who has worked with some of the Anaheim Angels, helped her get into even better shape. And Blankenfeld got serious about basketball again, at one point playing in three leagues in San Diego. In April 2000, with Blankenfeld approaching 32, another WNBA tryout beckoned in Portland, Ore. There were more than 100 players at the Portland Fire's free-agent camp, but Blankenfeld made an impression on a college coach who'd been hired to help with drills and evaluate players. "She stood out," said Dan Burt, who worked at West Virginia at the time and is now the recruiting coordinator at North Carolina-Wilmington. Burt asked Blankenfeld where she had played her college ball and was stunned to hear she had never played. He thought: Here's a recruit for us. Burt, who is two years younger than Blankenfeld, had no idea how old she was. He figured 19 or 20. She was 31 at the time. "When I found that out I had concerns because of the NCAA," Burt said. Under a rule that affects only Division I schools, athletes who participate in any organized sports competition past the age of 21 lose eligibility for each year they have played. Blankenfeld's years playing in adult recreational leagues had cost her precious time. So Burt began looking at other options and called Ken Patrick, then the women's coach at Seminole Community College in Sanford, Fla. "I've got a player here who is probably going to be one of the best you've ever had," Burt told Patrick. "It's a little different story." Patrick wasn't fazed by Blankenfeld's age. Community colleges tend to attract "non-traditional" students and student-athletes: 7-footer Janna Kotova of Estonia and 6-9, 28-year-old Susie Gyarfas of Hungary had previously played at Seminole. Patrick called Blankenfeld in California and asked her if she had ever thought about playing college basketball. She said no, but he persuaded her to come for a visit. "Her basketball was a little rusty," Patrick said. "But her conditioning far exceeded any 18- or 19-year-old I had." Blankenfeld proved to be an outstanding find. She averaged 13.7 points, 6.3 rebounds and three steals per game while shooting 52.9 percent from the field and was freshman of the year in the Mid-Florida Conference--at 32. She was also an outstanding student, achieving a 4.0 grade-point average, which led to a spot on the junior college Academic All-American team. Wilkes, the veteran Rollins coach, knew what was going on just north of his school, but he was leery of bringing in junior-college players. "I watched her play several times, because it took a lot to convince me that we could incorporate her into our system," he said. But Wilkes needed some immediate help for a team that would be one of his youngest. So he put aside his doubts and offered Blankenfeld a full scholarship--that's $32,600 a year at this pricey institution. "I wasn't convinced until we got into practices," Wilkes said. "She's done a great job of blending in, and I didn't think it was possible." Mary Lou Johnston, a 20-year-old sophomore from Winter Springs, Fla., was an all-state high school player and a USA Today honorable mention All-American before enrolling at Rollins. "When Gabby came in for a recruiting visit, we knew she was older--maybe 26, 27," Johnston said. "When we found out how old she really was, we thought, `For an old girl, she's really tough.'" Blankenfeld not only plays young, she looks young. During halftime of Rollins' 65-54 loss to Armstrong Atlantic of Savannah, Ga., earlier this month, a fan in the stands at the Alfond Sports Center on Rollins' campus was surprised to learn one of the players on the court was 34 years old. She guessed No. 45, Randi Weiss, a Rollins sophomore who had just turned 20. Blankenfeld averages 7.2 points and leads the team in free throws made and attempted (15-for-19). She played 19 minutes against Armstrong Atlantic and wound up with six points, three rebounds, a steal and a block as Rollins suffered its first loss in seven games. Her mother has seen her play at Seminole and will be traveling to Winter Park next month to watch her for the first time in a Rollins uniform. "It's so exciting," Sue Berndtson said. "It's just like watching your child go through it the first time." Copyright © 2002, Chicago Tribune

|